Traces of Ice

science, poetry, and personality in imagining the Ice Age

The duality of ice, its unyielding power and its vulnerability, intertwine in the musical and physical structure of postWinterreise. In a performance that embeds art within environmental cycles, and their disruption, ice, stone, water, and metal transform and meld with the music of Franz Schubert's Winterreise. With its world premiere at Tanglewood, this project begins its path on ground that bears witness to a world shaped by ice.

A geologic trail terminates in the soil beneath Tanglewood.

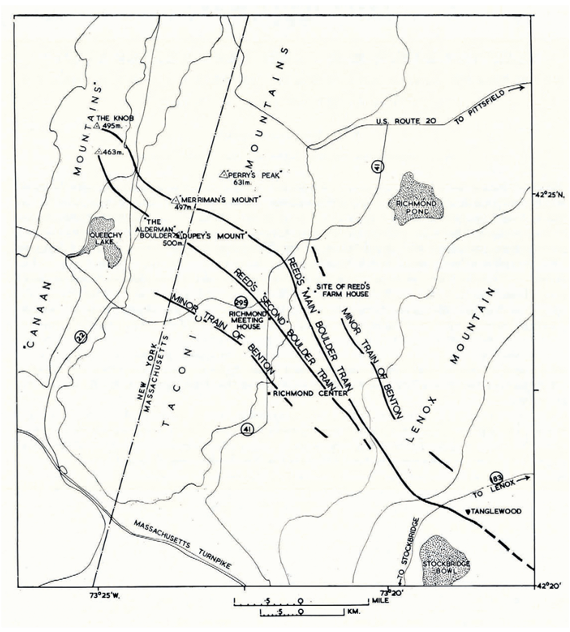

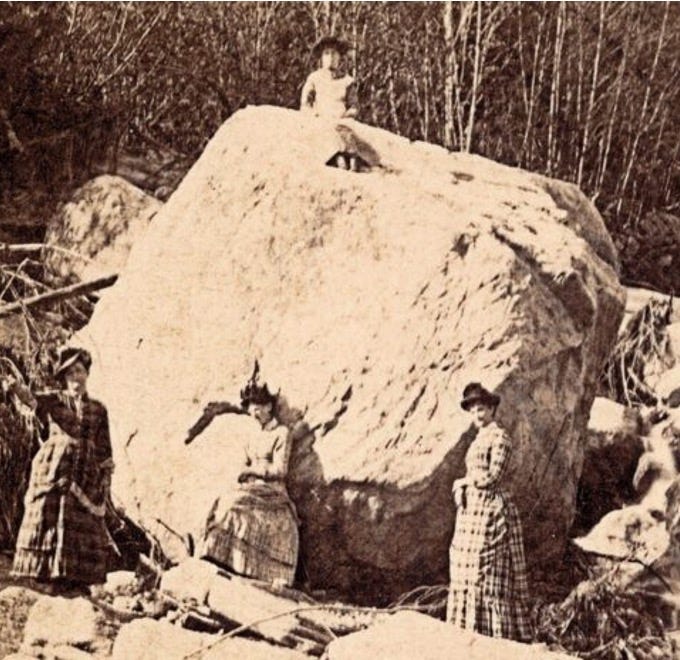

Large stones, lithographically distinct from the limestone bedrock, rest silently on the grounds and forest on the Stockbridge Bowl's shore. They are the tail end of a twenty-mile string of out-of-place boulders, spreading over the Berkshires and Taconics, to their source in New York's Canaan Mountains.

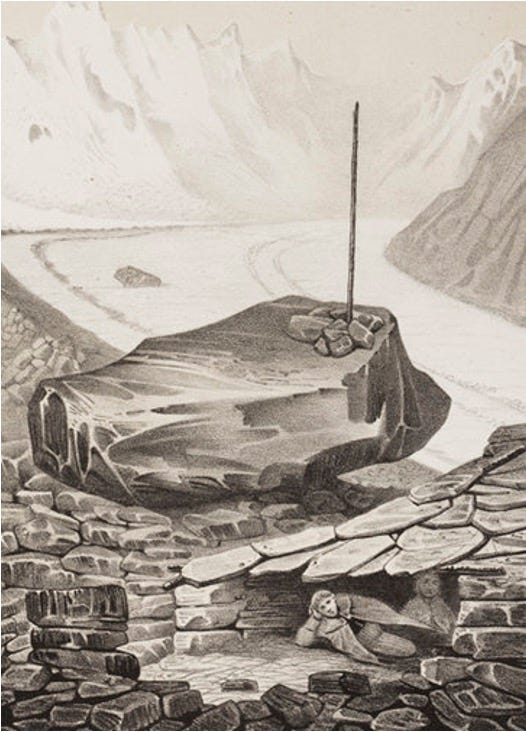

When first documented in 1842, this "boulder train" provided a geologic riddle: what force could break stone from a hilltop in New York and crumble it to pieces spread across the landscape? Across the Atlantic, similar puzzles of displaced stones broken from low-elevation rock formations and strewn up steep mountain slopes were observed by scientists, and poets, in the Alps.

In 1837, the naturalist Karl Friedrich Schimper turned to verse to describe these boulders, and the geological history from which they emerged.

Emerging from deep beneath the ground,

the Alps broke through the weight of ices,

whose frozen train, endlessly rubble-filled

with boulders which still strangely adorn mountain crests.Drawn to these boulders initially to study mosses that grew atop them, Schimper became embroiled in the debate over the boulder's origins. Unconvinced by explanations of vulcanism or flooding, Schimper formulated a new theory. Not only were the boulders in strange places, sheer rock faces that rose from the same valleys were scraped. A solid mass, capable of not only moving, but shaping stones, was at work. Schimper thought it was ice.

His poem was a lyrical panorama describing a past era in which the ice caps of the far north extended their reach across Europe, submerging even the Alps beneath frozen water.

Primeval ice from times when the force of frost

Buried even southern lands mountain-deep

Covering peaks and seas alike!He titled his poem The Ice Age (Die Eiszeit). The name, scientific and colloquial, for periods in which glaciers extend across the Earth’s surface, was a poetic invention. From its advent in our consciousness, the image of a world ruled by ice elicited a response both scientific and artistic.

The year prior to writing The Ice Age, Schimper had spent the summer with Swiss colleagues, Jean de Charpentier and Louis Agassiz. Studying the boulders of Switzerland's Rhone Valley, Charpentier had reached a similar conclusion as Schimper, and the pair eagerly shared their observations and theory of an era in which the Alps were encased in ice with Agassiz. Fossilized fish had drawn Agassiz to the Alpine region, and upon hearing the work of his colleagues, he realized the explanatory power of their unpublished observations far outweighed the grandeur of fossilized fish.

Ever the opportunist, in 1837, Agassiz presented Schimper and Charpentier’s ideas and research in a lecture for the Swiss Society of Natural Research. He credited neither of them, going so far as to recite from Schimper’s poem.

The explanatory power of the theory of glaciation to unite seemingly disparate geologic phenomena brought its recognized progenitor renown, and in 1847, a professorship at Harvard. Better known than Agassiz' plagiarism of colleagues in Europe, is that upon immigrating to the United States, he used his scientific pedigree and personal charisma to advance pseudoscientific claims of white supremacy. Whether there is a parallel to be made between Agassiz’ self serving professional ethics and his search for a scientific justification of racial hierarchy is beyond the scope of this writing. Saima S. Iqbal's 2021 article in the Harvard Crimson Louis Agassiz, under a Microscope, details Agassiz' racism and its legacy.

Until the recent awakening of liberal institutions to their complicity in American racism, Agassiz' image as pre-eminent scientist in the mold of Alexander Humboldt remained largely unquestioned in public.

But he had found an early critic in Schimper. To vent his anger at Agassiz' scholarly poaching, Schimper penned these words in the poem Mountain Formation (Gebirgsbildung):

Galilean torture is inflicted upon the singer of the ice age,

The target of thieves, condemned, ruined,

While Agassiz chatters as a thieving magpie to the crowd

Naive, stupid, dumb they applaud his marvels.Although it may have been melodramatic of Schimper to liken his predicament to Galileo's persecution by the Catholic Church, his work on glaciation had a similar effect of dethroning the human. Just as a heliocentric model of the solar system removed the human from the known universe’ centerpoint, a world in which familiar landscapes were once encased in ice, could not be said to be for humans any more than it could be said to be for the mosses that had initially captured Schimper’s attention. That this world-altering insight was attributed to Agassiz, never let Schimper go. For it was he, and Charpentier who had scoured the Alpine valleys and called the more prominent scientist's attention to those errant boulders and their glacial origins.

Still they rest upon fire-forged rocks, shipwrecks of a past age

They heaved themselves upon the Alps, the host of glaciers,

Whose hesitating retreat laid down the blocky moraines.The Ice Age was Schimper's only published work on the era he named. Agassiz beat Charpentier to the press, publishing his Study on Glaciers in 1840, overshadowing the latter's 1841 publication Essay on the Glaciers and Erratic Terrain of the Rhone Valley.

The following year in 1842 the amateur geologist Stephen Reed put forth a far more modest publication in the Lenox Farmer which described a twenty-mile chain of erratic boulders across the Berkshires. The landscape now covered in maturing secondary forests was then deforested for grazing livestock, construction in cities of the Eastern Seaboard, and fuel them with a supply of charcoal. With its forests peeled away, the boulders perhaps stuck out as anomalous, defiant of the newly delineated property lines and state borders.

Already home to a milieu of European-American intellectuals and artists, the Berkshires and the boulders described by Reed were an inviting stage for the nineteenth century’s leading scientists to advance competing theories of geologic history.

In 1872, Agassiz weighed in on those incongruous boulders strewn across the hills and country estates of western Massachusetts. In Observations on boulders in Berkshire County, he drew a parallel between glaciation in the Alps and the Berkshires, suggesting that the stones had been deposited not by mega storm or prehistoric seismic activity, but by the retreat of a continent-spanning ice sheet at the end of the ice age. Agassiz' publication was an echo of a proposal made decades prior in 1847 by Pierre Jean Édouard Desor. He was Agassiz' traveling companion and secretary, when he had proposed that it was the retreat of the continental ice sheets that had strewn boulders across the land.

The remnants of this ice sheet, the Laurentide, which once covered the Stockbridge Bowl in a mile of ice near its southern terminus, sit on Canada's Baffin Islands as the Barnes Ice Cap. A recent study from the University of Colorado indicates that the last of this primordial ice will have melted in three hundred years.

The theory of glaciation is a recognition of ice's power to shape the world. Composed in the decade that scientists scoured the Alps to make sense of errant boulders and their relationship to the glaciers lingering in the valley heads, Schubert's Winterreise depicts ice as a reflection of an over-powering and inescapable grief. It defines the wanderer's world. Two centuries after its composition and that early fieldwork, ice again inspires grief. It is threatened. Glaciers, the last fragments of the ice age’s continental ice sheets, have become symbol and evidence of climate change's existential threat. As in the moment of first apprehension of a past defined by ice, our present reckoning with an iceless future, elicits a response both scientific and artistic.

postWinterreise will premiere at Tanglewood on April 25, 2026.

postWinterreise is a project of the interdisciplinary production hub A Circle. A Circle is a fiscally sponsored project of Fractured Atlas. To support interdisciplinary collaboration, research, writing, and recording, please make a donation: